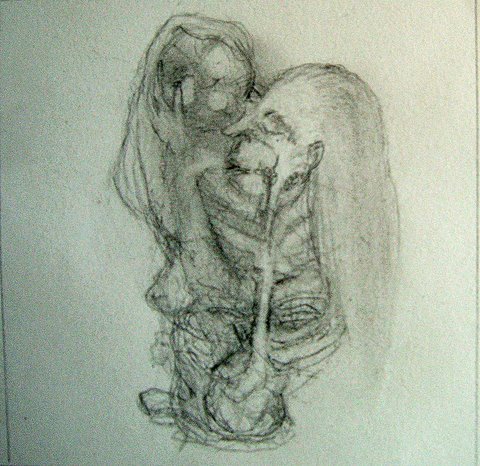

"I look at the world like a simultaneity of past lives and personas. It

started when we got back from Italy and were first living in Brooklyn. I

was working at that paint shop Sirmos in Long Island City. You remember

the Citicorp building, the lone blue green glass monolith that at that

time was the only building of that height and stature in that area. I

was walking to the G train after work. It was end of summer early fall

and the sky had dramatic Turner/ Frederick Church type clouds and I was

struck by this overwhelming feeling that I had lived this before. That I

was some artisan in the service of some king or something, and that

Citicorp building was some ziggurat. It was beyond overwhelming, like

two lives superimposed over each other, identical."

I remember you spoke about this moment-- at the foot of the ziggurat,

of blue glass. I’ve had similar experiences -- in many places. I

feel attuned to this kind of resonance. Your message also got me thinking about why we get anchored into the past as archetype? Why do we want to forget the future? What if we look at time all wrongly? Rather than the Ziggurat as template for Citicorp,

what if Citicorp was the previous life of the Ziggurat? Or are we

always in the same situation or scenario and the names only change?

Why don't we know the future name for this structure? If we knew the

name could we not re-name it, change it? Is there no escape? Is there

anything our creativity can to do to alter things or is it already

written in some kind of fossil?

By implication, if I interpret a bit what you say, it

seems to me we are always in the shadow of some pyramid, megalith,

volcano, oppressive market system, government. Some source of shock

and awe. But I seriously wondered about the thought process that

keeps us snapped into our trapped dimensionality here.

Why can't they see the vision nor hear the music?

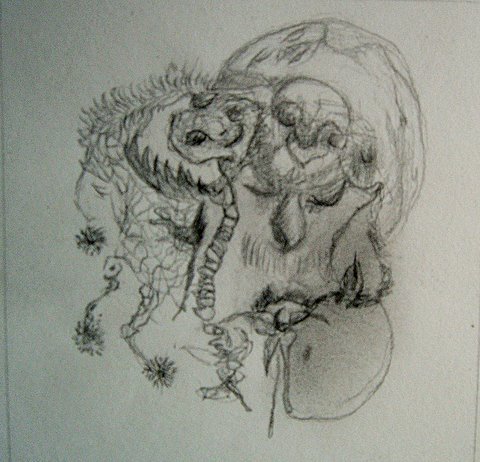

I have been having dreams I don't want to wake up from where

everything is very good humored and always morphing. Seriously having

a good time being Morpheus and the Mother of Morpheus. What keeps me

from being able to communicate this sense to people? Why can't they

see the vision nor hear the music? Thinking about your Citicorp and

Ziggurat as two incarnations or configurations of archetype, I asked

myself again the question about time and, if it is possible, to see

around the corner of the megalith. What does it rest upon? There are

suns far larger than our own. And Gaia has her own body-mind. Still,

the human fixation is such that it can become nerve-wracking and

frustrating.

I'm thinking about, hey, why don’t we get a future

“glimpse” or sense of what’s coming out of this kind of moment,

because it’s as if we could walk into the next manifestation of

this identical or parallel scenario. Or bypass it. If we only knew

how. What

if we are already the future, that future we would rather be be and

just don’t know it?

Why can't I go out dressed magically?

Buddhist and Vedic meditators melt time into ooze evaporating into

transparency -- "all the time".

So what? Why can't I go out dressed as a magically mirror-faced

four-legged walking wardrobe with constantly changing hair color

cracking jokes in a language whose rules of grammar are being made up

as each foot falls into the span of wing that sweeps away into some

plasma naming itself via movement? Is that not what is happening? Why

are we bound to this brain-span that is “getting a job and walking

the walk?’

What is a Boltzmann Brain?

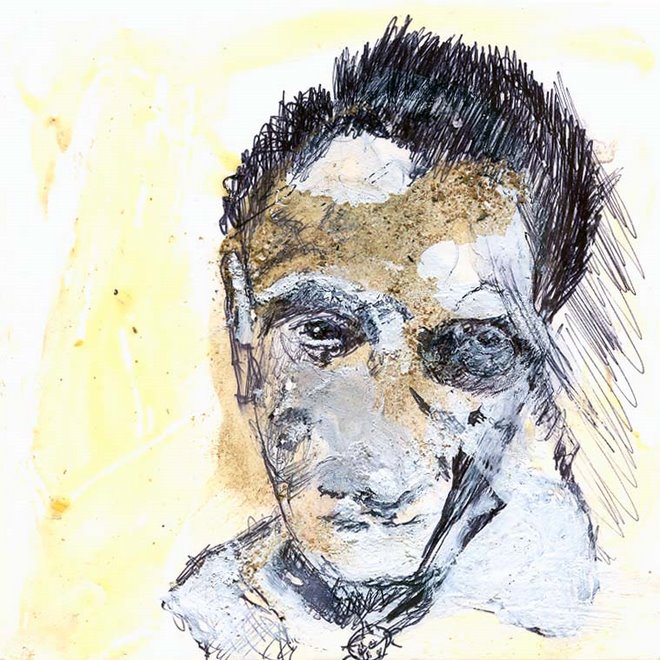

Anyway, even before this so-called morning, I went to sleep

after reading an article that maybe your Citicorp/Ziggurat stardust

put in my way via synchronicity. About the Boltzmann Brain. The

thrust of the paper was multi-tiered, co-authored by three science

geeks, so I cannot cram it into a few sentences. But one thing they

wanted to show was that the classical Newtonian second law physics of

entropy that results in this hypothesis that there is a Past moment

(previous state), the Past Hypothesis, that is not any different from

the Boltzmann Brain hypothesis, which states that a brain can exist,

exactly like mine or yours, with all it's experiences and memories

firmly in place while being created by entirely random combinations

of elements and forces of the universe in millennia of evolution.

This Boltzmann Brain would be your brain but without you. A pretty

strange idea. The paper discusses how the role of circular reasoning

in the Boltzmann Brain is in exactly the same circular reasoning used

to justify the Past Hypothesis (where there is some historically or

scientifically verifiable version of reality, with a starting point

and an endpoint -- like the Big Bang. So basically the Boltzmann

Brain Hypothesis called into question all theories about memory.

Memory is a memory of a memory. How an event got stored as a memory

of an actuality is subject to the law of entropy. The further away

you go into time, the more it is just memory of memories. It became

such a maddening thought that I hit google maps, plugged in the

address of the house I lived in with my parents in 1970’s, where

father’s parents lived upstairs (also with Babcia Florence)

upstairs, a house that had belonged to the previous generation of the

family, 416 Walden Ave, Buffalo, Neuvo Yawk. I did this search because I

recall it was still standing years ago, unlike other Buffalo houses

where I or other family had lived, razed after fires, cleared. I

found 416 Walden Ave there on the street view. The surroundings had

changed but the house itself looked structurally unchanged from the

outside. I felt pretty sure I could still map the inside, sketch it

out for anyone. I still can walk in this house of my memory. And yet,

boom, there it was: I could not verify any of this. Probably never

will be able to. If I could however, it would not allow me to

change the past because it must always be that way. But will this

house always be as it is? It seems highly improbable but it is a

question of structure: 416 Walden has a large-basement and strong

foundation. It stands because it has this solidity of stone. Monolith. I also

noticed the house two doors away, which in the old days was the

domicile of the family of the caretaker of the Concordia Cemetery, it

too still stands. This house connected to the Stability of Death and

its burial grounds rooted like it’s trees into the soil and

culture. 416 Walden Avenue was said often to be a haunted house. They

meant ghosts of the past and perhaps traumatic events. I wonder if

the house was not actually haunted by it’s Future. Why does my mind

return there so often? If the power of my thought is that strong to

haunt, I should have more money in the bank. This of course is taking

things a bit too far.

Regarding Boltzmann Brains:

https://www.santafe.edu/news-center/news/disentangling-the-boltzmann-brain-hypothesis-memory-entropy-and-time