listen here by the click

https://soundcloud.com/jeff-gburek/the-problem-of-our-laws-op-389-201

is there too much music? too many people? too many ideas? or

not enough love? there are so many things one could say. one of which is

there are too many opinions and look here comes another one although look at how it

adds up to a kind of polyphony of noise

these things I say inside the noise above

-- among the noise of other things and peoples --

one can't deal with the overload as an individual. Either there

there really really is is too too too too too too much information or there is in fact no information at all. oh no...

one model of communication asserts that the person has to already know the

message they are seeking in order to be able to receive the message when it is

sent. this is why there is a tremendous amount of nostalgia posting about the

music of the past, as if we are seeking a reassuring narrative and through this

the message we've conditioned ourselves to look for will undoubtedly arrive. In

this sense there's not too much music but not enough anti-music.

Herbert Brun's

idea was that it is only in anti-communication that the composer creates the

condition in which the listener must find a meaning or a message that has not

been predetermined

Many complain that the words of the wise are always merely parables and of no use in daily life, which is the only life we have. When the sage says: “Go over,” he does not mean that we should cross over to some actual place, which we could do anyhow if the labor were worth it; he means some fabulous yonder, something unknown to us, something too that he cannot designate more precisely, and therefore cannot help us here in the very least. All these parables really set out to say merely that the incomprehensible is incomprehensible, and we know that already. But the cares we have to struggle with every day: that is a different matter.

Concerning this a man once said: Why such reluctance? If you only followed the parables you yourselves would become parables and with that rid yourself of all your daily cares.

Another said: I bet that is also a parable.

The first said: You have won.

The second said: But unfortunately only in parable.

The first said: No, in reality: in parable you have lost.

BUT, HOLD ON A MINUTE! Q: WHAT'S THIS ALL ABOUT?

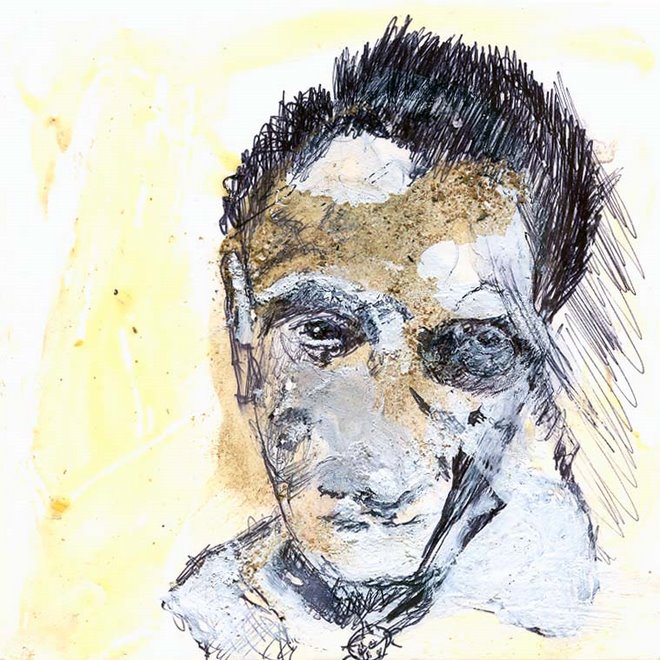

The Parable of the Problem of Our Laws, written by Franz Kafka, sprang to mind (--> wiki link -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Problem_of_Our_Laws ) -- within the howl of these recent images from Gaza, it shook my mind, again. These impressions combined with the messages streaming through Olga Tokarczuk's recent Nobel Prize speech -- all flowed together in this new sono-podcast, this evolving audio-poem, with synthesizer, shortwave radio, percussion, voice, performed live in the studio. Some words are my own gathered up from scraps of paper and given breath again but the vast majority belong to a passage of Olga Tokarczuk's text (see footnote). The other messages recombine as new sensations, margins of electromagnetic information. With thanks to Karolina Ossowska --without whom I'd have likely not read Olga's work and a special thanks to Tom Carter for the "is there too much music" question, which sparked again the movement towards the anti-music, the unanswerable question...

https://soundcloud.com/jeff-gburek/the-problem-of-our-laws-op-389-2019

"The Problem of Our Laws" (German: "Zur Frage der Gesetze")

The story is a short narrative, where laws of the land are described as esoteric, created by the elite. Thus, being such they are out of the hands by the common people, yet binding. Nobility is seen as the authority, the creator and executor of laws, yet completely separate from those whom they apply to. Yet, these laws create a sense of security among those who follow them, an empty one, since they are in fact a type of cruel joke. Incidentally, the story echoes the labyrinthine system of law and regulations in place among the official in Kafka's earlier novel, The Castle

Olga Tokarczuk -- Nobel Prize Winner in Literature for 2018 -- she writes:

"The flood of stupidity, cruelty, hate speech and images of violence are desperately counterbalanced by all sorts of “good news,” but it hasn’t the capacity to rein in the painful impression, which I find hard to verbalize, that there is something wrong with the world. Nowadays this feeling, once the sole preserve of neurotic poets, is like an epidemic of lack of definition, a form of anxiety oozing from all directions."

Today our problem lies—it seems—in the fact that we do not yet have ready narratives not only for the future, but even for a concrete now, for the ultra-rapid transformations of today’s world. We lack the language, we lack the points of view, the metaphors, the myths and new fables. Yet we do see frequent attempts to harness rusty, anachronistic narratives that cannot fit the future to imaginaries of the future, no doubt on the assumption that an old something is better than a new nothing, or trying in this way to deal with the limitations of our own horizons. In a word, we lack new ways of telling the story of the world.

We live in a reality of polyphonic first-person narratives, and we are met from all sides with polyphonic noise. What I mean by first-person is the kind of tale that narrowly orbits the self of a teller who more or less directly just writes about herself and through herself. We have determined that this type of individualized point of view, this voice from the self, is the most natural, human and honest, even if it does abstain from a broader perspective. Narrating in the first person, so conceived, is weaving an absolutely unique pattern, the only one of its kind; it is having a sense of autonomy as an individual, being aware of yourself and your fate. Yet it also means building an opposition between the self and the world, and that opposition can be alienating at times.

Paradoxically, however, this situation is akin to a choir made up of soloists only, voices competing for attention, all traveling similar routes, drowning one another out. We know everything there is to know about them, we are able to identify with them and experience their lives as if they were our own. And yet, remarkably often, the readerly experience is incomplete and disappointing, as it turns out that expressing an authorial “self” hardly guarantees universality.

What we are missing—it would seem—is the dimension of the story that is the parable. "

"The Problem of Our Laws" (German: "Zur Frage der Gesetze")

The story is a short narrative, where laws of the land are described as esoteric, created by the elite. Thus, being such they are out of the hands by the common people, yet binding. Nobility is seen as the authority, the creator and executor of laws, yet completely separate from those whom they apply to. Yet, these laws create a sense of security among those who follow them, an empty one, since they are in fact a type of cruel joke. Incidentally, the story echoes the labyrinthine system of law and regulations in place among the official in Kafka's earlier novel, The Castle

Olga Tokarczuk -- Nobel Prize Winner in Literature for 2018 -- she writes:

"The flood of stupidity, cruelty, hate speech and images of violence are desperately counterbalanced by all sorts of “good news,” but it hasn’t the capacity to rein in the painful impression, which I find hard to verbalize, that there is something wrong with the world. Nowadays this feeling, once the sole preserve of neurotic poets, is like an epidemic of lack of definition, a form of anxiety oozing from all directions."

Today our problem lies—it seems—in the fact that we do not yet have ready narratives not only for the future, but even for a concrete now, for the ultra-rapid transformations of today’s world. We lack the language, we lack the points of view, the metaphors, the myths and new fables. Yet we do see frequent attempts to harness rusty, anachronistic narratives that cannot fit the future to imaginaries of the future, no doubt on the assumption that an old something is better than a new nothing, or trying in this way to deal with the limitations of our own horizons. In a word, we lack new ways of telling the story of the world.

We live in a reality of polyphonic first-person narratives, and we are met from all sides with polyphonic noise. What I mean by first-person is the kind of tale that narrowly orbits the self of a teller who more or less directly just writes about herself and through herself. We have determined that this type of individualized point of view, this voice from the self, is the most natural, human and honest, even if it does abstain from a broader perspective. Narrating in the first person, so conceived, is weaving an absolutely unique pattern, the only one of its kind; it is having a sense of autonomy as an individual, being aware of yourself and your fate. Yet it also means building an opposition between the self and the world, and that opposition can be alienating at times.

Paradoxically, however, this situation is akin to a choir made up of soloists only, voices competing for attention, all traveling similar routes, drowning one another out. We know everything there is to know about them, we are able to identify with them and experience their lives as if they were our own. And yet, remarkably often, the readerly experience is incomplete and disappointing, as it turns out that expressing an authorial “self” hardly guarantees universality.

What we are missing—it would seem—is the dimension of the story that is the parable. "

No comments:

Post a Comment